|

| Digimon Adventure: V-Tamer 01, Chapter 16. The sign reads "Jump D-1 Grand Prix." Volcano Oota appears in the back. |

At birth,

Digimon was a fundamentally competitive idea. A fighting

Tamagotchi. Consequently the franchise has a long history of tournament organization, primarily centered around the one mode of play that can be described as quintessentially

Digimon; the dot matrix toys. Organized competition has evolved over time to encompass a number of media that aren't strictly played on LCD screens, but even those media do generally adhere to the rules and mechanics first established by Bandai in 1997. When you consider the hardware history of the virtual pets, there's a clearly articulated line of descent originating with

Tamagotchi and descending on down to the modern

Digimon World -next 0rder-. To western

fans, the franchise can often be a distant and

elusive thing, created and maintained by a team of opaque and faceless

foreigners. This is a consequence of the language barrier, of the lack

of immediacy between franchise-changing events in Japan and their

consequences overseas, and of the number of hands that have repeatedly

modified the franchise for the west. I want to eliminate that distance

, closing the gap between artist and audience or writer and reader. In some regards that distance is already shorter for Portuguese-speaking and German fans, who have already circulated much of this information in their own languages. So by

naming names and telling histories, I hope to bring

Digimon closer to the English-speaking fanbase.

My other purpose is cultural transmission. I wish to pass down to newer fans the things that they were not present to see. It seems apropos to talk about them now that

-next 0rder- is upon us. Of course, the world is not divided into just Japan versus an abstract "west." There are many more perspectives that could appear here, but I cannot speak from the perspective of the Korean fandom, or of the Puerto Rican fandom, or any of the myriad other groups that exist in this history. I will write this from two perspectives that until recently only existed on the periphery of one another; Japan and the United States. These are the two stories that I feel qualified to tell.

|

| Oota Kensuke in-character as "Volcano" Oota at a 2014 anniversary event. Original image uploaded by totuzenhi. |

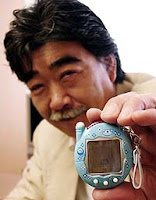

The dot matrix games were the brainchild of the Digital Monster Series Planning & Development team (デジタルモンスターシリーズ企画開発

Dejitaru Monsutaa Shiriizu Kikaku Kaihatsu).

Names to know include project head Oota Kensuke (太田健介) as well

as Digital Monster designer and artist Watanabe Kenji (of WiZ). Both of these figures continue to work on

Digimon in the present, most recently having a hand in the 2014

Digivice Ver. 15th toys. In the west Watanabe has a small cult following, while Oota is practically unheard of.

|

| Maita Aki in 1997, age 30. |

Digimon is one of the few 90s monster series that can claim a legitimate line of descent simultaneous to or predating

Pokémon. One could say that

Digimon indirectly owes its birth to the state of the Japanese housing industry. The franchise originates from the

Tamagotchi, conceived of in 1994 or '95 as a solution to apartment-wide bans on pet ownership.

Maita Aki (真板亜紀) is the original concept holder and designer, but beyond the initial concept Aki was primarily involved in marketing and had little to do with the actual development process of either

Tamagotchi or

Digimon. This is one reason why Maita is rarely credited in Japanese sources as having contributed to

Tamagotchi; real development was handled by Yokoi Akihiro (横井昭裕) from WiZ and several others from Bandai, while Maita (also from Bandai) focused on the sales and data end.

These days the fact that it was Maita who came up with the idea of a portable pet is often forgotten, and in Japan she's primarily known for the Ig Nobel Prize she was awarded for "diverting millions of person-hours of work into the husbandry of virtual pets." She's presumed to still work at Bandai, and occasionally modern photos of her with new models of Tamagotchi surface.

Hongō Akiyoshi is frequently credited with the original concept for

Digimon, but this is for the sake of convenience. Hongō is not a real person, but a house name created by Bandai to ascribe an original copyright holder without having to divide the copyright between its original contributors. The name is often said to be derived from the names of Hongō Takeichi, a co-director at WiZ co., formerly Bandai's chief "Tamagotchi officer," and Maita Aki. (An alternative explanation uses Nakatsuru

Katsuyoshi's name, see below.)

Portuguese Wikipedia suggests identifying Hongō Akiyoshi with five people: Hongō Takeichi, Maita Aki, Hiroshi Izawa, Yabuno Tenya, and Nakatsuru Katsuyoshi. Hiroshi is the original writer for the manga

Digimon Adventure V-Tamer 01, while Yabuno is the illustrator, and Nakatsuru was responsible for the character designs and animation direction of

Adventure,

Adventure 02,

Tamers, and

Frontier. The Hongō name in general is associated with

Digimon's evolution into a multimedia franchise.

The reason these five are identified with the Hongō pseudonym is because of how closely the related

Digimon properties were being developed prior to their launch in 1998~'99. The preproduction phase of

Digimon involved

V-Tamer 01,

Adventure, and the theatrical film all being developed simultaneously by intercommunicating staff. This is how the decision to make Yagami Taichi the main character of all three works came to pass despite several different companies having their hands in the various works. Regardless, the Hongō group isn't very relevant to where we are beyond their overlapping membership. Its formation took place

around the time that Digital Monster Ver. 5 was launched, when the first plans for an anime series were being laid.

The members of DMSPD became the original monster makers. Oota led the team up through 2000. The first Digital Monster virtual pets were patterned after a cage, keeping the monster locked up.

According to a 2014 interview with Oota, the original documentation and data from the first run of Digivices no longer exists, and so it's likely that the initial Digimon program as it was created back then met a similar fate. This is a result of poor data keeping practices among Japanese electronics developers up until around 2006. Like with the lost

Kingdom Hearts data over at Square Enix, Bandai no longer has any plans nor documentation from these devices. Ironically for a company producing a fiction oriented around a digital world, Bandai failed to digitize their work.

Conceived of as artificial life born in the manmade wilderness of electronic information networks, it seems only natural that Digimon--obeying the law of the jungle--would take years to develop the same level of complexity and nuance as their Game Boy cousins. The original Digital Monsters were brutally simple and strongly chance-based, first launched in five waves in June 1997, December, March 1998, May, and August. Where

Tamagotchi saw a 60-40 split in female to male consumers,

Digimon took off with elementary boys and junior high students. As a result of its coverage in

Young Jump and

V Jump magazine, the virtual pets were highly anticipated prior to launch and started off strongly with the public.

Digimon World -next 0rder- character designer Taiki

once recounted standing in line at a department store on launch day for the virtual pets, a moment that still stood out for him eighteen years later. One month after, Hiroshi Izawa and Yabuno Tenya published the one-shot manga

C'Mon Digimon in

Shounen Jump NEXT!!'s 1997 summer special. The comic was later reprinted as an

omake chapter in

V-Tamer 01.

It is important to see Digimon not just as a game played by children, but as the comprehensive imaginary world it cultivated in the minds of those players. On a cosmetic level, the pets had a sense of individuality from the wide variety of colors they came in, and the individual backgrounds each pet had to represent key areas. Also referred to as landscapes (風景

fukei), these are no longer found in modern virtual pets, as the backgrounds were discontinued beginning in July 2002 and were fully phased out in 2004. Digital Monster Ver. 1~5 had five possible areas--plains for Ver.

1, wasteland for Ver. 2, a forest for Ver. 3, mountains for Ver. 4, and a

beach for Ver. 5. The areas were not actually electronically projected, but instead created using

an old trick developed by the arcade industry. By printing sheets of

cardboard backgrounds that could then be cut to fit the screen's dimensions, and inserting them behind the display of each device, the dot matrix characters could be projected in front of the landscapes, giving the illusion of a world in a box. This also had the advantage of making the characters more visible under direct lighting. These

environments gave each tamer a specific area to identify

with, personalizing the virtual pet experience. For its day this was an immersive look into Bandai's proposed digital world.

Bandai also took in fan submissions during the creation process of these pets, resulting in Hououmon (originally Kujimon), Kabuterimon, Angemon, Yukidarumon, Birdramon, and Veggiemon all being selected from a pool of 50,000 entrants in a December 1997 design contest. There were also seventeen different colors of v-pet: two versions of red (Ver. 1), two versions of blue (Ver. 1), green (Ver. 1), yellow (Ver. 1), black (Ver. 1), white (Ver. 1), smoke (Ver. 2), clear (Ver. 2), purple (Ver. 3), orange (Ver. 3), clear purple (Ver. 3), clear orange (Ver. 3), clear blue (Ver. 4), clear red (Ver. 4), and clear green (Ver. 5). In addition to these, a number of limited edition virtual pets exist.

A Primer on Pendulum Evolution

For various reasons, the majority of the western Digimon fanbase is unfamiliar with the form of evolution used in Digimon's null canon. Nicknamed "Pendulum evolution" after one of the more popular later virtual pet models, unlike the evolution featured in the anime series, these evolutions are

permanent changes that take place as a Digimon matures into increasingly more battle-oriented forms. What a Digimon evolves into in the virtual pets is controlled by how well it is raised, just as was true for the Tamagotchi pets that served as the inspiration for the LCD games. A "care mistake," failing to respond to a Digimon's needs like hunger or sleep quickly enough, will impact which of the three or more possible stages it can evolve to. Evolution is not reversible; the only way to go back to the Child stage after attaining Adult, or back to Adult after attaining Perfect, is by dying and raising a new Digimon. If a Digimon has been raised well at the time of its death, it reincarnates into a "traited egg," a Digitama that will hatch into a new Digimon but with improved probability to survive to its subsequent evolutionary stages. (Usually this is a 10% bonus; in the console games it manifests as inheriting a percentage of the deceased Digimon's stats.)

When the pets were brought over to the United States in 1997, the Japanese names for the different evolutionary stages underwent some creative translation. Where the Japanese names reflect the idea of maturation throughout a lifecycle, the American names framed Digimon as competitors and gave a boxing-like overtone to the series.

Japanese stages (Romaji) / American "translations"

Baby I (Younenki I) / Fresh

Baby II (Younenki II) / In-training

Child (Seichouki) / Rookie

Adult (Seijukuki) / Champion

Perfect (Kanzentai) / Ultimate

This later created problems with the official translation of the Ultimate (

Kyuukyokutai) stage when it was created in 1999-2000, as a result of Perfect being translated as Ultimate for the United States. The English translation adopted by Bandai US for Ultimate ended up being Mega, which isn't really a translation at all.

Kanzen has a meaning of "completeness/perfection" while

Kyuukyoku means both "the strongest" and "the last."

For years the primary competition in

Digimon was Bandai's officially-organized series of tournaments, the D-1 Grand Prix, which was so named to take advantage of public consciousness surrounding the F1 Grand Prix and K-1 karate competition. (The K-1, having originally been hosted in Japan in 1993, had a particular presence at the time.) Billed as a series of battles to determine the strongest Digimon tamer, the tournaments were emceed by "Volcano" Oota, also known for his Digimon Corner columns in both

Weekly Shounen Jump and monthly

V Jump magazine. Beginning in August 1998, the prize for winning the tournaments was a D-1 special edition Digital Monster Ver. 4.

Ten thousand of these special edition devices are known to have been distributed, as well as gold tamer tags. Elementary, junior high, and high school students were all eligible to participate.

According to V-Tamer's Residence--an unofficial but highly respected Japanese source for information on

Digimon--the first D-1 tournaments actually began in April (announced on March 26th, 1998) and ended on August 23rd of the same year. At this time D-1 included the Digital Monster Ver. 1 virtual pet (May 1997), Ver. 2 (December 1997), and Ver. 3 (March 1998) bringing in a total of 42 Digimon to the tournament series' roster, though in practice only the nine Perfects were viable for winning a D-1. The tournament series started out with

Weekly Shounen Jump &

V Jump magazine's Spring Digimon Festival (春のデジモン祭り

Haru no Dejimon Matsuri) on March 26th, which took on the title of J D-1 Grand Prix (J・D-1グランプリ

J D-1 Guranpuri). A panel from chapter 16 of the

V-Tamer manga shows the D-1 labeled as "Jump D-1 Grand Prix," and seeing as the two

Jump magazines were the tournament's co-sponsors, this explains the appended J.

These initial D-1 tournaments were acknowledged on the

Digimon Channel website (prior to its revamp in 2002) as collectively part of the "D-1 All Japan Tournament." In chronological order the first events were;

D-1 All Japan Tournament

Jump D-1 Grand Prix II

D-1 Grand Prix Regional Tournaments 1998.11

Mac Donald Adventure Digimon Tournament 1999

Sadly, the official tournament reports for every event listed above have been lost to time. The Internet Archive never captured those pages prior to the site's revamp, so the names, ages, photos, and partner Digimon of the winners are presumably gone forever. There's no use dwelling on this; unless Bandai or WiZ still has the old site information on file or someone with archives of the pages magically appears, we'll never know the results. At this time Bandai was also making some efforts to coordinate the

Digimon brand through the official website, in their first BBS system "DigiCafé." Moderating DigiCafé proved difficult as both the toy and home internet exploded in popularity, leading Bandai to close the BBS' doors within a few years.

Although the monster Etemon was introduced in the Ver. 3 pet at the beginning of the month, the current

personality we recall when we think of Etemon was put together as a promotion campaign for the D-1. "Digimonkey" was a mascot character that first appeared in

Shounen Jump's

Digimon-centric column

Weekly Digiki (週刊デジ聞

Shuukan Dejiki, using the character

聞

ki for "to hear"), promoting the D-1 tournaments. Various incarnations of Digimonkey would continue to appear until the mid 2000s.

Digimonkey was set up in opposition to Volcamon, a Digimon embodying the D-1's emcee "Volcano" Oota, the host personality created by the DMSPD team leader who has since rebranded his character as "Pile Volcano" Oota. Oota is one aspect of the D-1 that would go on to outlive the tournament series; in 2000 the popularity of his personality led to Volcamon's formal debut as a real Perfect-level Digimon, which in 2002 got an Ultimate-level upgrade, Pile Volcamon. Oota has continued to work for Bandai in promoting the series, hosting their events every year since '97, and taking up the mantle of the character once again in 2014 to promote the

Digivice Ver. 15th. Exactly why Oota stuck with the brand for so long is unclear, but in a 2002 in-character interview he stated that his final goal was for

"Everyone in the world to love Digimon." Was Oota being sincere? As the man who was continually listed as the project leader to the present day, he's always had a vested interest in promoting his creation to the world. And given his enthusiasm for being an entertainer, it seems Oota had a genuine love for the children he worked with.

Several months after the close of the first D-1 tournament, D-1 was used as a supporting element in

V-Tamer 01 (Taichi and Neo were both participants) and an "Etemonkey" version of Etemon, based on Digimonkey, was used as a key antagonist. This version of the character comes off as more sympathetic in

V-Tamer when you're already aware of Digimonkey's positive role in promoting D-1. In the manga, Etemonkey was an Etemon motivated to go to the real world so he could play with human children, and served as a minion of Demon in hopes of achieving that. Izawa and Yabuno's readership would have been exposed to Digimonkey on the very pages of the magazine that was serializing their manga, creating a media link between the different portrayals of Etemon.

By today's standards, the original Digital Monster virtual pets were highly affordable, retailing for just 1980 yen prior to tax (or $20 in US money). Participation in these tournaments was thus very accessible to Japanese children, and flyers packaged with each Digital Monster alongside

V Jump promotions ensured high public awareness of the D-1. This was how I first encountered the Grand Prix years after its conclusion, through a photograph of a flyer for the tournament taken from a mint condition virtual pet. In order to qualify for the national championship finals, participants needed to win regional qualifiers held across Japan. This is a very common model for tournament organization in Japan, especially with regards to children's events, but what set D-1 apart from both contemporaries and present-day equivalents was that the D-1 tournaments were all held inside of high-profile department stores. The locations made an effective marketing strategy for Bandai, as consumers could observe the tournament proceedings within the stores and then go and buy digital pets right off the shelves of the locations.

As a result of the tie in advertising campaign, we have a semi-complete list of tournaments held from June through September, comprising fifteen regional qualifiers and the national finals. The names on this list imply the existence of at least two other tournaments that were held prior to June, in Kantō and Ky

ūsh

ū. Given that five tournaments per month were being held throughout the remaining season, it's likely that there were at least five tournaments held in both April and May, and only one in March. Hence the number of regional tournaments was somewhere around 26 in total, capped off by the finals. (The April 1997 issue of

V Jump magazine should have a complete listing of all D-1 tournaments for '97 and '98. However, scans of that issue are nowhere to be found and it's questionable if any copies have survived to the present outside of

V Jump's own personal archives, which have not been digitized.) All of these locations are still in operation today, and in the case of the Sogo department stores this is somewhat miraculous. Sogo collapsed in the early 2000s as a result of poor investment policies, and not all of its locations have persevered under the current Sogo & Seibu management.

D-1 SERIES LOCATION SCHEDULE

06/06/98: D-1 Hokkaido Tournament 1 (北海道) Sapporo Tōkyū, 250 participants

06/07/98: D-1 Hokkaido Tournament 2 (北海道) Toys' Yoshida in Asahikawa, 500 participants

06/14/98: D-1 Naka-ku Tournament 1 (中区) Fuji Grand Hiroshima Shopping Center, 250 participants

06/21/98: D-1 Kantō Tournament 2 (関東) Machida Tōkyū Department Store, 250 participants

06/28/98: D-1 Tōhoku Tournament (東北) Shirobotan Kids Walker (白牡丹キッズウォーカー) central plaza 2, 250 participants

07/19/98: D-1 Kansai Tournament 1 (関西) Kintetsu Department Store (近鉄百貨店), third event space, 250 participants

07/26/98: D-1 Kantō Tournament 3 (関東) Seibu Department Store (西武百貨店), fourth floor festival space (4階まつりの広場) 900 participants

07/26/98: D-1 Naka-ku Tournament 2 (中区) Hiroshima Sogo (広島そごう), rooftop (屋上) 250 participants

07/28/98: D-1 Hokuriku Tournament (北陸) Kanazawa Meitetsu Marukoshi Department Store (金沢名鉄丸越百貨店), 250 participants

07/30/98: D-1 Kantō Tournament 4 (関東) Kashiwa Sogo (柏そごう), rooftop (屋上) 500 participants

08/01/98: D-1 Kantō Tournament 5 (関東) Yokohama Sogo (横浜そごう), second floor pedestrian deck (2階ペデストリアンデッキ), 500 participants

08/06/98: D-1 Chūbu Tournament 1 (中部) Matsuzakaya Flagship Store (松坂屋本店), 250 participants

08/09/98: D-1 Chūbu Tournament 2 (中部) Meitetsu Pare Department Store (名鉄パレ百貨店), 250 participants

08/16/98: D-1 Kyūshū Tournament 2 (九州) Tsuruya Department Store (鶴屋百貨店), first floor satellite studio, 250 participants

08/16/98: D-1 Kansai Tournament 2 (関西) JR Kyoto Department Store (JR京都伊勢丹), 500 participants

08/23/98: D-1 JAPAN (All Japan Tournament) (全日本大会) Seibu Department Store (西武百貨店), fourth floor festival space (4階まつりの広場) 1000 participants

Each regional qualifier followed a single body of rules. Japanese manuals for the Digital Monster pets identified the preliminary rounds of each D-1 as a best-of-one games Battle Royale format, and the top cut as a best-of-three tournament bracket. This meant that participating tamers only needed to win a single game each round to proceed initially, but anyone that lost a game during the preliminaries would be cut from the tournament entirely. Exactly how many tamers the top cut consisted of is uncertain, but it must have contained at least two. Those tamers would then play a best-of-three set, with the Digimon that won more games coming out the winner.

|

| The second Naka-ku D-1 qualifier was held here 17 years ago. Photo taken by Kitaro. Bird's-eye-view by tamahata767. |

The largest of these regional qualifiers was held at the Seibu department

store's Kant

ō location, while the most exotic was probably Hiroshima's and Kashiwa's

tournaments at their respective Sogo department stores; these tournament were held

on the rooftop. Sogo is famous for its rooftop playland attractions, which each feature an all-in-one arcade, playground, restaurant, and minor goods shopping center. (In recent times, the rooftop grounds have been repurposed as beer gardens for late-night events. Since a lot of young Japanese men and women have fond memories of the playlands from childhood, it makes sense to market the area to them as adults. Sadly, the Kashiwa location has since fallen into disuse, as outside of said garden events and its

hokora Shinto shrine, the rooftop is

completely barren today.) Coincidentally one of the D-1 qualifiers was held on Odaiba Day, two years before the day would be recognized as significant. The location was

not as spectacular as some of the others, but it was one of the largest tournaments of the season.

The national championship finals were hosted at the Seibu Department's fourth floor festival space on September 23rd, 1998, over an open-air bridge connecting the store's main building and annex. In addition to the participants invited from the regional tournaments, a number of locals were allowed to participate in order to establish the tournament cap of 1000 participants. The documentation available does not state how many from each regional were invited, but mathematically bringing in the top 4 from each of the 26 tournaments would create a minimum ~100 person competition, with room for the remaining 900 that attended the previous Seibu regional to participate.

By the time of the final tournament, all five

of the original virtual pets were in circulation. Unlike today, there were only five standard evolutionary levels, not six: Baby I, Baby II, Child, Adult, and Perfect. Out of the sixty Digimon available for tournament use, only fifteen of them were Perfect-level Digimon, and of those only five were "S-Rank" Perfects likely to

go undefeated, what guides have categorized as group L Digimon. To elaborate,

each of the sixty Digimon that could be battled were

categorized into one of twelve groups, each with a particular base

probability to win a battle versus one of the other groups. This

probability was internally measured as X/16. The group a Digimon belonged to was visually identified by the type of shot it produced in battle; all group L Digimon shot hearts, all group A Digimon shot triangular fireballs, all group B Digimon shot lightning, and so on. When a Digimon was created, its in-universe special moves were tailored to the type of shot produced on the virtual pet. This is why all of the top tier Digimon listed below have attacks like "Lovely Attack," "Unidentified Flying Kiss," and "Love Serenade." The attacks needed to match the heart sprites.

Group L had the best overall matchups

with every other group, having an average 12/16 or 75% chance to win

versus any given Digimon. Its worst matchup was with itself, which was

only an 8/16 or 50% chance to win. This was the highest probability to

win versus a group L Digimon of any group. In other words, the best

counter to group L was other group L Digimon, hence there was no real

reason to use any Digimon other than these five if one was able to do so.

The five group L Perfects were Monzaemon (Ver. 1), Vadermon (Ver. 2),

Etemon (Ver. 3), Digitamamon (Ver. 4), and Ex-Tyrannomon (Ver. 5). These

five Digimon dominated the competition, and were essentially

interchangeable save for aesthetics. Limited access to them came from their obscurity and difficulty of raising them, as each group L Perfect evolved from a group I Adult, the weakest overall group with an average 25% chance to win versus any given opponent, and the only way to guarantee an evolution to Perfect was to have a high win ratio in addition to meeting the basic requirements of having 15+ battles at either the Child or Adult stages. It was a lot of work to raise one of these Digimon because the best Perfects in the game evolved from the worst Adults--Numemon to Monzaemon is the most famous, but for the other pets it was Veggiemon to Vademon, Scumon to Etemon, Nanimon to Digitamamon, and Raremon to Ex-Tyrannomon.

|

| Chinese guide to the twelve groups and their respective probabilities. |

The outcome of a battle wasn't purely up to your Digimon of choice. There was another way to increase one's probability of winning, by repeatedly feeding a Digimon protein to build up its chances by a maximum of 20% of the original value, but as a whole these were contests of who could

raise the best and not of who could battle the best. The elemental triangle of Vaccine > Virus > Data > Vaccine was not implemented in these pets, but a primitive form of it existed at the Adult level. Group C Digimon (Greymon, Kabuterimon, et al.) had an advantage versus group G (Airdramon, Birdramon et al.), which had advantage against group D (Devimon, Angemon, et al.), who in turn had that same advantage versus group C. Occasionally you'll find the argument that real competition lay at the Adult level rather than at Perfect, because it introduced this type of metagame. But since only one Digimon could be raised at a time, there was no way to strategically capitalize on these triangular relationships. (Note that the terminology changes from place to place. For example,

this Japanese evolution guide correctly sorts all of the Digimon into their respective groups, but also places the Baby I and II Digimon that cannot battle into their own categories, which causes group L to be referred to as group N, A as C, and so on.)

We do not know the name of the first D-1 Grand Prix national champion, nor do we know their partner Digimon, or how the final game played out. But we can infer some facts about it. Each Digital Monster pet was essentially a cosmetic reskin of the Version 1 pets, with no gameplay differences under the hood save for one fluke involving Deltamon's care requirements in Ver. 4. Battle thus played out identically across different models; each Digimon spent three rounds firing shots at one another and taking the opponent's blows, then in round 4 the winning Digimon fired a double shot and dodged the opponent's. The influence of protein items really came from how protein influenced power level, a hidden value ranging from 0 to 2. Eight proteins raised power level by 1, and became ineffective after the first sixteen proteins were given. The structure of the D-1 effectively selected for whichever tamers were using group L Digimon, and from among those whichever ones fed their Digimon the most protein. (For additional reading on the first generation virtual pets, With the Will user BladeSabre

did some further research, primarily confirming the existence of power level and verifying current knowledge of how protein influences a Digimon's likelihood to win. His data generally matches up with that published by

V-Tamer's Residence.)

The D-1 tournaments spawned their own culture, legends, and memorabilia in the Japanese

Digimon community. Those legends obviously can't be verified due to a lack of any

recordings of the event proceedings, but the fact that these stories

were circulated at all is perhaps more notable than their veracity. One

example is of a Numemon

defeating an Andromon

in an official tournament on a Ver. 1 Digital Monster pet versus a Ver.

3, which only had a base probability of 6% to happen at all. At each of the D-1 events Bandai began selling tamer tags--also referred to as tamer licenses--each of which featured a unique serial number, the D-1 logo, and a different Digimon on the front. The serial numbers were wholly unique, and like the virtual pets themselves were designed to give each tamer a distinct identity. They were intended to be worn with the keychain pet attached to the chain, and for added security Bandai also produced a line of "cages," plastic hinged cages equivalent to the modern phone case that protected the screen behind another layer and left open access to the buttons.

This type of material culture helped spur the early growth of the

Digimon community in Japan, and the tournament series as a whole was pivotal to helping

Digimon gain steam with the general public. The virtual pets were primitive, rough around the edges, and very chancey; but they were also wildly popular and captured the public imagination just as

Tamagotchi had done a year earlier. Bandai helped foster community further through the internet, using their official

Digimon Channel website to host "Digimon Café," a specialized chatroom for tamers. Café would remain in operation until early June 2003.

One month after the end of the first Grand Prix, the lines on what constituted

Digimon first began to blur. On September 23rd the franchise's first console game,

Digital Monster Ver. S: Digimon Tamers launched on the Sega Saturn, recreating the virtual pet experience in full color and on a home system that allowed for up to four Digimon to be raised simultaneously and battled in a virtual world. The game mimicked the appearance of an advanced home computer at the time, like the then-prominent iMac G3 and its OS9. What's interesting is that the game was launched as if it was just another addition in the Digital Monster lineup; here you have Ver. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and S. The game's Digimon lineup primarily comes from Ver. 1~4, with some game-original additions, and like the Ver. 2 Digimon, three of the five hacker antagonists were originally designed by readers of

Weekly Shounen Jump and monthly

V Jump; Pirate Hacker, Superhero Hacker, and Funky DJ Hacker. 50 other entrants were chosen to have their names used for the Scrub Hackers (ザコハッカー) the player faces.

Having played

Ver. S I can attest to its quality and general faithfulness to the original gameplay mechanics, though it's debatable as to whether it's more or less so than

Digimon World. It was also the first

Digimon product to feature File Island, and a concrete storyline, pioneering a minimalist BBS/e-mail/system error mode of storytelling three years before

Uplink and twelve years before

Digital: A Love Story would make this device famous. (And when

Ver. S was using these narrative conceits, the technology was

new rather than retro.) The story in

Ver. S is delivered in chunks of messages read in the player's inbox and seen on simulated webpages, with dialogue only appearing when confronting one of the hackers the player is competing with.

Seeing the massive Digimon sprites plead for food, express anger or happiness, and go head-to-head is a delight. However, as video game

Ver. S hasn't withstood the test of time. The novelty of seeing virtual pet sprites done justice as detailed full-body animations on par with arcade tech and rendered on a home console has been done better by later games. The storyline is thin, the music dated, and the controls are made for another era. The game's biggest sin is its lack of multiplayer options, as the core storyline makes for a ~5 hour maingame and the primary appeal of the

Digimon pets as opposed to

Tamagotchi is pitting your own best work against your friend's best work.

Digimon World would remedy this, leaving

Ver. S in obscurity.

In spite of its flaws,

Ver. S fascinates by how subsequent history articulates it as the first in a long line of console successors to the virtual pets. Chief producers Asanuma Makoto, Inagaki Hirofumi, and Imanishi Tomoaki all went on to work on

Digimon World. The majority of

Ver. S' staff continue to work on

Digimon games today, although part of this is because

Ver. S had a very small credits roll. Individuals like director Shindo Takayuki, who seemingly never worked in video games again, were the exception rather than the rule.

Ver. S paid homage to its origins, listing the DMSP team in its special thanks; Hongo Takeichi, Oota Kensuke, Horimura Ayofumi (Given name reading uncertain; 堀村有由文), Suzuki Toshihiro (鈴木

敏弘), Satou Takeshi (佐藤剛司), and Uchiyama Daisuke (内山大輔). Interestingly, Watanabe Kenji was credited as a shareholder from WiZ rather than as an illustrator, alongside Kitagawahara Shin (北川原真) and the more-familiar Yokoi Akihiro. Digimonkey gets his dues right at the end of the credits roll. (The character allegedly appears in the game using Etemon, but I've never seen him in any recorded playthroughs, and didn't get to a point in my own where he'd appear.)

The simplicity of the Digital Monster pets was a weakness in gameplay terms, but later years would show that it was that very simplicity that made it appealing to a significant audience of consumers in the first place. Having taken off with elementary school children and junior high students,

Digimon was well on its way to becoming a major media presence. During the development of the Ver. 3 Bandai began commencing the first major talks with Toei and Shueisha that would branch into the creation of a multimedia franchise. Plans for the second Grand Prix were in the works as the first one was ending. October of 1998 would bring the first major revisions to the digital pet formula, beginning a move away from flat gambles on percentage chances, and towards a more skill-based, tamer-driven system for commanding Digimon.